The Massachusetts Medievalist on Inferno, Cantos 16-18

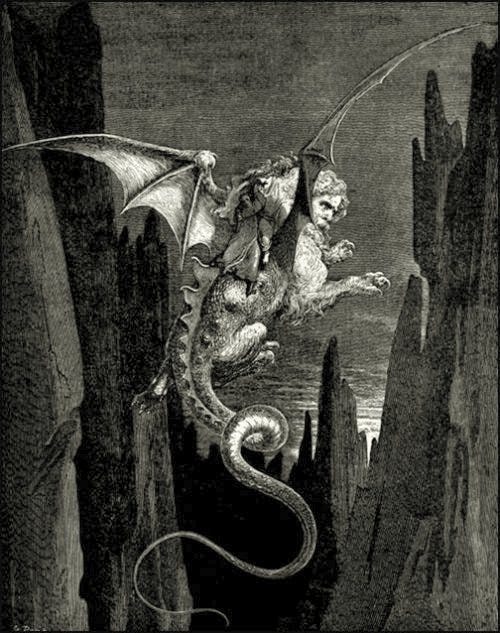

This week I'll focus on Geryon, an important Hellish monster who provides what I think is the most cinematic of Inferno's episodes. These three cantos take us from the seventh circle (with its three rings) to Malebolge, the eighth circle (with its ten pouches). Note that Dante coined the term Malebolge which translates literally to "evil pouches." Geryon unifies these three cantos: he is summoned in 16, provides transportation in 17, and embodies the theme of 18 and all of Malebolge. The eighth circle houses the fraudulent sinners, and Geryon is a massive and monstrous symbol of deceit. Doré provides two illustrations of Geryon:

from World of Dante and Wikipedia, respectively

The usual critical reading of Geryon focuses on the way that he embodies fraud - he is "fraud's foul emblem" (17.6) in that "His face was a just man's face, outwardly kind" (l.9) but he has hairy arms and paws, a colorful snake's body, and a scorpion's tail. So he looks "kind" in the front but has deadly venom in the back, in the same way that seducers and flatterers (those we meet in canto 18) seem sincere but are deadly in their treachery. Virgil, who symbolizes goodness and reason, protects Dante from Geryon's tail during the descent (17.74-75): Reason thus protects Humanity from Fraud.

Allegorical and philosophical readings aside, this episode provides an exciting action sequence. Dante is so terrified of the monster that he is shivering; he tries to speak and can't. This is perhaps not the most conventionally heroic of presentations -- contrast with Beowulf jumping into Grendel's mere or Gilgamesh brawling with the Bull of Heaven -- but it's very human and very understandable. Despite the terror, the journey itself seems dreamlike and wonderful (in the archaic meaning of "full of wonder"). Geryon's tail "churned / The way a swimming eel does" (17. 94-95) so that suddenly the atmosphere of Hell becomes water, with Virgil and Dante riding on a water-monster's back. Dante the poet continues to play with our understanding of elements throughout the sequence, as Dante the pilgrim tells us that "I was in sheer air --/…but the beast, Onward he swam…" (17.102-105), creating an air-water contradiction that does not seem contradictory in the moment. Geryon's slow, wheeling descent into Malebolge is so sensory and detailed that I had no trouble imagining it as a great scene in an action film. I'm sure numerous film makers have attempted it; I'm also sure their work can't match the wildness and elation in my head when I read this part of canto 17. The canto ends with an abrupt transition back to the more usual tempo of the narrative: "he did not wait / But vanished like an arrow from the string" (17. 126-127).

One final point about Geryon: conventional critique groups him with the other composite monsters of Hell - the harpies, the centaurs, etc - but he's also oddly parallel to the Angel who unlocks the gate of Dis in Canto 9. I'd even argue that Geryon is a foil for the Angel, in that they have enough similarities that their differences become even more important. Dante is separated from Virgil, however briefly, during the sequences with both beings; neither Geryon nor the Angel speaks to Dante and Virgil; both are gigantic, supernatural beings who have the power needed to allow Dante and Virgil to continue their journey. All this overlap then emphasizes their crucial difference: that the Angel is temporarily in Hell but not of it, while Geryon is a permanent fixture both literally and figuratively. Dante took Geryon's name but little else from classical mythology, inventing his own Fraud monster to castigate those who commit this sin and do not repent.

William Blake, Geryon, via Blake Archive

Possible items for discussion:

Is Dante the pilgrim learning anything along his journey? Do you see him as a dynamic or static character so far?

The first and second pouches of Malebolge are differentiated but they are also so similar that Dante conflates the seducers and the flatterers from different pouches into one canto - how do seduction and flattery overlap?

Note that the early circles are dedicated to sins of "incontinence" (lust, gluttony, sloth) while the deeper circles contain the sins of heresy and violence and fraud. According to Dante's schema, why are these worse? And do you agree with that judgment? (this question relates to our discussion of last week about culpability, sin, and mental illness)

With this week's Cantos, I feel like I finally saw some real progress for Dante as a dynamic character. There were two instances that stood out to me as moments of "growth." In Canto XVII, before approaching Geryon, Virgil instructs Dante to go off on his own temporarily to observe the souls on the boundaries of Circle Seven. Dante obliges, which in my opinion is a big change from the gates of Dis, where Dante begged Virgil not to be left alone.

Though I doubt we'll see much change in Dante in terms of strength or bravery, because I think the whole point is that Dante's Hell is too terrifying for mortals to overcome. I think the real change here is how Dante is viewing/interacting with the souls he encounters along the journey. I'm noticing a transition from pity to scorn in Dante's conversations with the souls he encounters. For example, in Canto XVIII Dante recognizes and speaks harshly towards Venedico Caccianemico in the first ditch of Circle Eight. I think this is where we will see Dante emerge as a dynamic character, as he moves from pitying the souls for their punishments, to judging them for the sins that got them there.

Thus far, I am seeing Dante as a static character. He has been blindly following Virgil through hell and making no choices or decisions of his own accord. While we do witness moments of self-examination and a peek into his emotional state, he does not seem to be internalizing what he is experiencing. It seems like each new circle of hell is seemingly a "fresh-start" and has no connection to his next leg of the journey. He is still heavily relying on Virgil not only for guidance, but for comfort and protection. In fact, when he was briefly left alone in Cantos 17, I was so shocked that I underlined the passage. Dante the pilgrim is still presenting as so humble and afraid, vastly differing from our typical view of a hero. While Dante is our protagonist, it may be fair to say that Virgil is more befitting of the title of "hero". I will note that physical strength and bravery do not need to be the only characteristics of a "hero", and I am interested to see if Dante emerges from hell with a new outlook on life and how he will internalize all that he has seen and learned. This, I think, will determine his "hero" status for me.