This week, we're in the seventh circle, dealing with some rough but important issues like suicide, the demonization of homosexuality, and violence. Sandow Birk's very cool illustrations of Dante's hell provide modern details while drawing on Doré's 19th-century engravings; here's his vision of the seventh circle:

Sandow Birk, The Seventh Circle of Hell, 2004, from Digital Dante.

This week's cantos also remind us of an important figure for the Comedy: Beatrice, who is invoked in the early cantos but then put off to the side for the rest of the journey through Hell. She's crucial for a lot of reasons, but I want to focus my remarks this week on the ways that she functions as a female figure in Dante's very patriarchal, very sexist universe.

Dante the Pilgrim remind us of Beatrice at 15.87-88, when he tells Brunetti that he (Dante) will wait until two prophecies "are glossed by a lady of good wit / And knowledge, if I reach her." This almost-throwaway line reminds us of the ultimate goal here - to get Dante through his quest so that he can spiritually reunite with Beatrice and get back on the right path, the one that will ultimately lead to Heaven and God (and Beatrice).

The historical Beatrice was a neighbor of the historical Dante; she died in 1290 when she was 24 years old (the Wikipedia entry for Beatrice Portinari is pretty comprehensive). In the Commedia, she represents "blessedness and divine grace" (notes to Pinsky translation, p.380) and she is invoked as both the muse and goal of the poem. In Canto 2, Virgil relays her charge to him in framed direct narration: so he speaks to Dante the words that she spoke to him. If we count this speech (and I do, though some academics do not), Beatrice and Francesca (the romance-reading adulteress we met in Canto 5) are the only women who speak in Inferno (for a comprehensive list and analysis of the women in Commedia, see Victoria Kirkham, 1989, A Canon of Women in Dante's Commedia).

So this is a problem hiding in plain sight. Most of the women in Inferno cluster in canto 5, which you'll recall is about lust. Like much of (men's) history and culture, Dante includes women primarily when the topic is Sex. Note that Francesca and Beatrice, our two speaking women, quite literally map onto the whore/Madonna binary that feminist critics have tried to get away from for the past 40ish years.

For the most part, Dante's Hell is inhabited by men and male figures. This isn't because, as some paternalistic scholars have argued, that Dante thought women were morally superior to men - it's because Dante views the world as primarily masculine by default. For Dante, the default human is a male human, and the universal human is a male human. He's not alone -- think of the classic example of Gray's Anatomy (the textbook, not the TV show!), which used to include images of the female body only in illustration of the female reproductive system.

We still live in a world where many of the defaults are male - an example I always use with my students is the fluidity of the phrase "woman writer" and the seeming oddness of the phrase "man writer." The ease with which we fall into the trap of masculine-as-default became apparent to me as I was reading this week's cantos and the reference to Beatrice jogged my brain out of its sleepy acquiescence to the all-male characters and voices of the Seventh Circle. I suddenly felt like Catherine Morland in Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey: "the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all!"

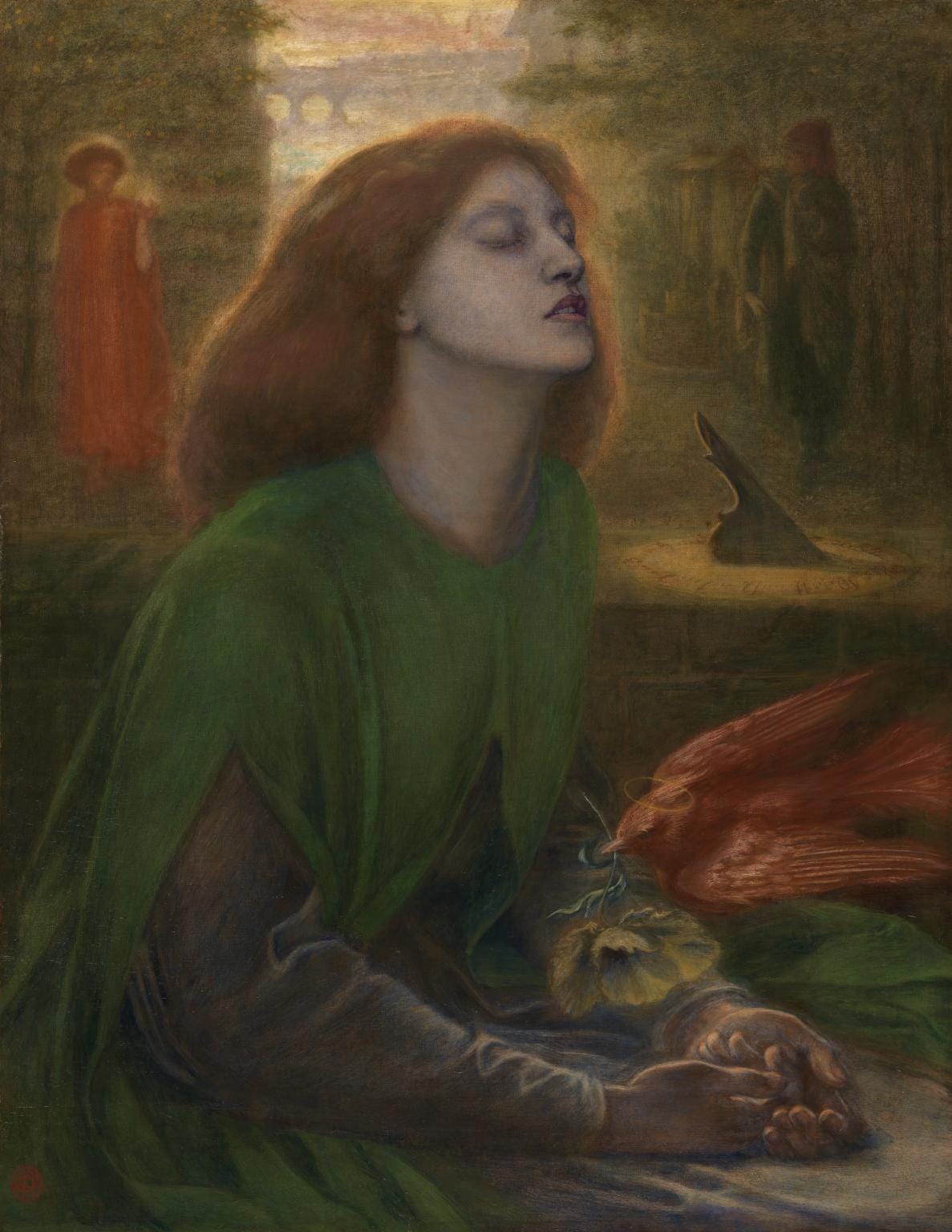

Rossetti, Beata Beatrix, 1864/1870, Tate Gallery

Possible items for discussion:

Extending our discussion of mental health + Inferno, how do we grapple with the wood of the suicides in Canto 13? Another famous, frequently-anthologized section of Inferno, it follows conventional Christian doctrine by classifying suicide as a sin, an idea that seems completely out of place in our twenty-first century context.

What were your reactions to Dante's conversation with Brunetti in Canto 15? This question is perhaps somewhat analogous to the one above, since "sodomy" may still be considered a sin in the Catholic church but non-heterosexual sex and relationships are (I hope!) now generally accepted in mainstream American culture.

What else were you thinking about this week?

is the label " paternalistic scholars" fair? aren't they just (misguidedly) trying to protect their hero? I have seen plenty of Blake scholars-both male and female - struggle to wash away Blake's sexism because they can't live with the obvious fact that their hero was not as they wish him to be.

it is also should be noted that Dante seems to find lust to be the one sin he has sympathy for--he must recognize that his feeling fo Beatrice was not untainted by lust!--though in la vita nouva he tries to convince himself other wise.

Considering modern understandings and views on mental health and suicide, I found Canto 13 to be a rather difficult read, one that didn't necessarily age well. I would be interested in reading contemporary religious interpretations of this part of Inferno to help reframe the wood of the suicides. I do see the parallels between this particular sin and its punishment; those who commit the sin of suicide, according to this text, forsake their bodies and are thus doomed to immobility in the form of a tree, never to regain their human form: "We can't put on our flesh, for Justice won't / Permit the repossession of the forms / We wilfully abandoned" (13.100-102). In my opinion, the cruelty of this punishment outweighs the sin. These souls who've committed suicide are unable to escape torment even after their deaths, when torment in life is what most likely drove them to the action. Also, their neverending cries of sorrow are helpless, which in a sense mirrors their cries for help in life. I feel like contemporary views on mental health and suicide make it difficult to reason with this harshness and see it as "Justice."

On a side note, I also thought it strange that Virgil felt he needed to first direct Dante to break the branch of a suffering soul in the wood of the suicides, in order for him to believe that there were souls inside the trees. With the chorus of wailing coming from this circle, and everything he's witnessed in the journey up until this point, I feel like Dante would be ready to believe whatever Virgil told him, without having to harm a soul that is already suffering. Virgil then apologizes and partly blames Dante's ignorance for having to do this? The whole exchange just had me scratching my head.