The Massachusetts Medievalist on Inferno, Cantos 22-24

I offer a deep dive this week into snakes, with more snakes featured next week as well! There were a lot of animals in this week's cantos, especially in the similes of Canto 22. Dante continues his use of familiar imagery to allow us to imagine hell: the sinners in the river of boiling pitch surface like dolphins (l.18), hop like frogs (l.25), or are caught like otters (l.34). The Malebranche continue to provide some humor, especially in Barbariccia's line, "Stand back, while I enfork him well" (22.57) - the Italian for that superb verb is 'nforco, in case you were wondering, and the demon's name translates to Curly-Beard.

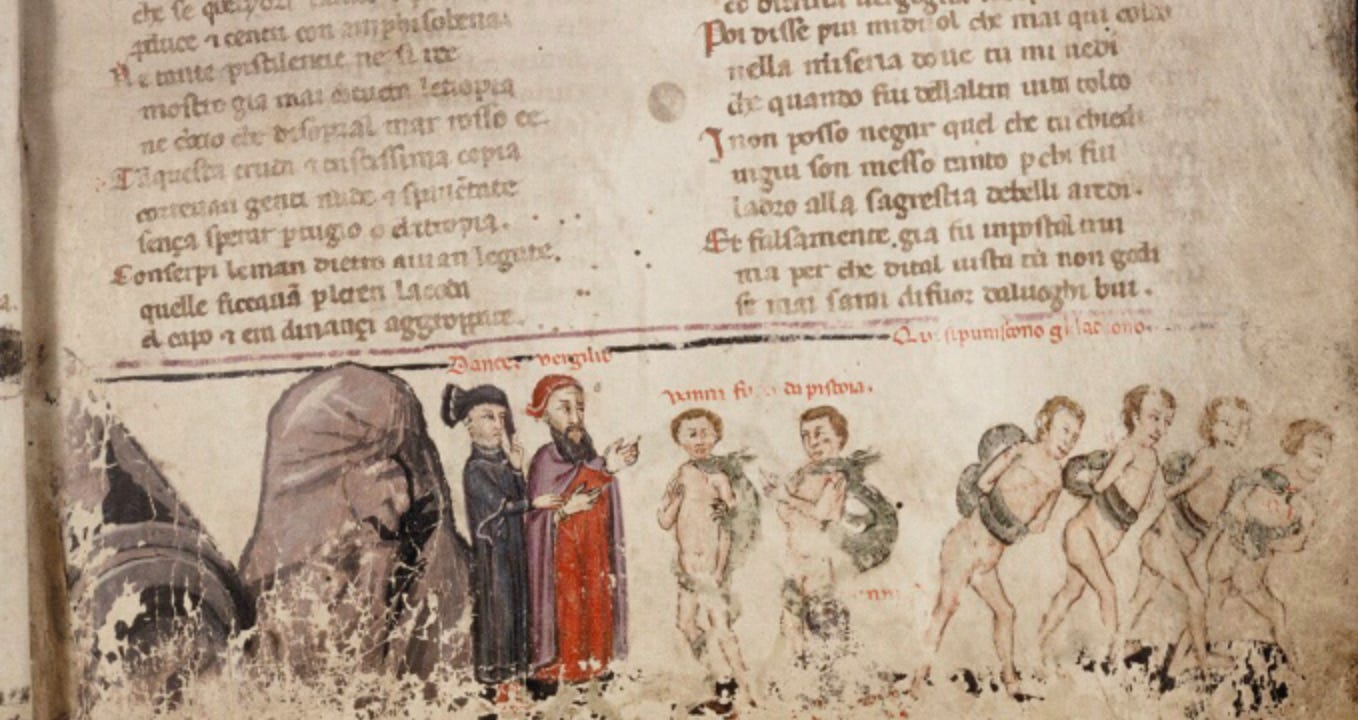

Oxford, Bodleian Library Holkham Msc.48, folio 37, from Digital Bodleian

But it's the snakes of Canto 24 that stand out for me this week. Pinsky follow the Italian cognate of serpenti (24.83) and uses "serpents" instead of "snakes." The slightly archaic word choice provides an elevated tone to the world of the seventh pouch, moving us from the grotesque humor of the Malebranche to a horror more immediate and more serious. I'm sure we all know the snake-response Emily Dickinson described as "zero at the bone," but we probably didn't use the word "serpent" when describing that fear.

There are so many snakes in this section of Malebolge that earth cannot match them in number or evil (24.90). They also do not behave like earthly snakes; the sinners'

…..hands were tied

Behind their backs - with snakes, that thrust between

Where the legs meet, entwining tail and head

Into a knot in front. (24.94-97)

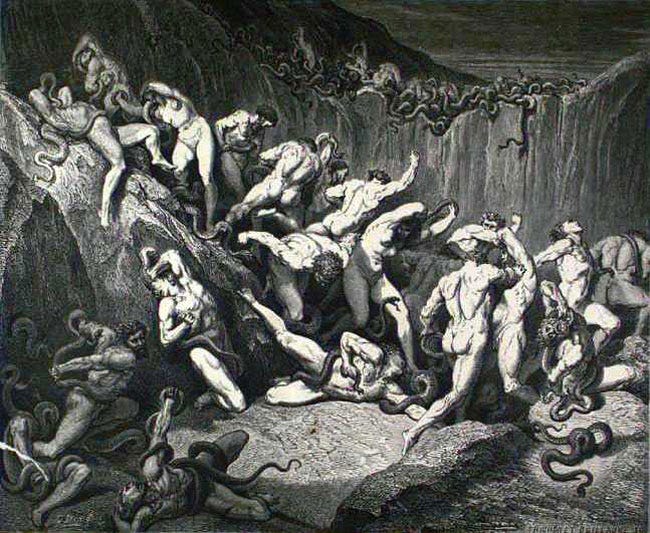

The Holkham manuscript (above) provides an idea of what this configuration might look like, as does Dore:

from World of Dante

And just after the lines quoted above, we discover that the bite of these hellish snakes induces a Phoenix-like incineration and resurrection, with the sinner reconstituted only to be entwined and bitten again.

The snakes here are operating on at least two levels. One is the visceral, human response that most of us have to snakes, the primal fear that makes us "zero at the bone" when we see even a garter snake. It's hard to read about snakes acting as ropes to tie hands together without the reader squirming at the description. So Dante is again here using common human emotion to bring us through Hell with him.

Symbolically, however, we also have to remember all the meaning that accrues to snakes through human texts and mythologies.Most important, of course, is the Snake in the Garden of Eden, the symbol of evil and deceit in Paradise (Dante would have known St. Jerome's Vulgate version of the Bible; Genesis 3 linked here in Latin with English translation). The sinners of the seventh pouch are thieves, so they are tormented by the animal that embodies their sin - just as they stole from their fellow humans, Eden's Serpent stole innocence and paradise from Adam and Eve.

The serpent also symbolizes immortality, however, and that symbolism layers intriguingly with evil and deceit. Adam and Eve lost the chance at immortality when they were expelled from the Garden. Snakes have also symbolized immortality or constant rebirth in numerous world cultures - their ability to shed their skins has given them a reputation for eternal youth as well as eternal life. Remember that a snake steals the flower of immortality from Gilgamesh in the final episodes of the Epic of Gilgamesh (Dante would not have known this narrative) and that snakes were associated with medicine and healing in numerous ancient cultures, including Greece (which Dante would have known). Dante has manipulated and combined these various meanings, however, so that the immortality of the snakes manifests itself in the "immortality" -- or eternality -- of Hell, that these thieves will be eternally tormented by symbols of evil, the snakes that God decreed would have "enmity with the woman."

Possible items for discussion:

Birk changes the "jovial friars" into a series of civil servants: how do you think the secularization of our society has affected your reading and understanding of Inferno?

Why do the Malebranche fight among themselves? On a related point: why do they turn on Dante and Virgil, despite Virgil's reminders that the travelers are protected by God?

The extended simile of Virgil like a mother 23.35 is oft-cited, oft-discussed in criticism of Virgil as a crucial character in Inferno. Specifically: how did it affect your understanding of Virgil and his relationship with Dante? Generally: how did it affect your understanding of gender in Inferno?