The Massachusetts Medievalist on Norman Rockwell's Misplaced "Feminism"

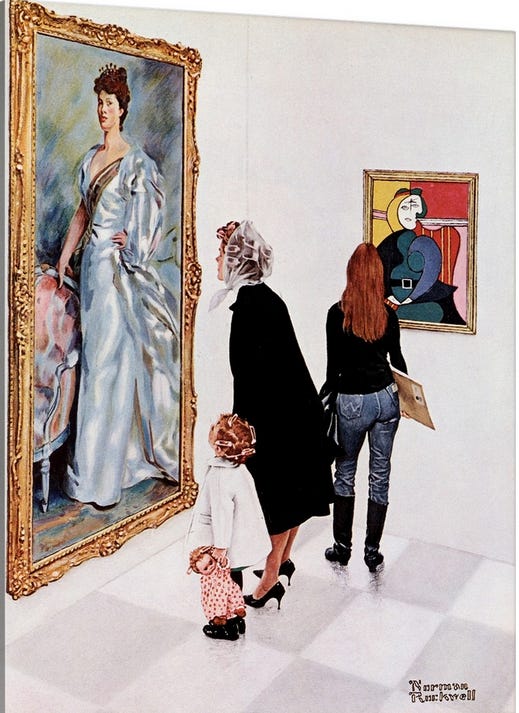

The Massachusetts Medievalist always enjoys visiting the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge MA; the curators there do a great job swapping out the collection, so there's always something new to see from this prolific artist in the lovely, small space. This past weekend, I was intrigued to see part of one gallery devoted to "Women in the Popular Press," which included an illustration from the 11 January 1966 issue of Look magazine titled Picasso vs. Sargent:

It's an entertaining image, set in a fictional art museum that hangs Sargent's Mrs. George Swinton (actually at Chicago's Art Institute) catty-corner to an imaginary Picasso that Rockwell created as an amalgam of the plethora of Picasso's paintings of Marie Therese Walter. Check out the Norton Simon Museum's Woman with a Book as an example of these images. Walter is generally referred to as Picasso's "mistress" or his "muse," both now cringe-inducing terms in the era of #MeToo and the impulse towards gender-neutral language. He certainly did paint her a lot (Picasso Marie Therese Walter is an enormously satisfying google image search).

The women viewing the paintings are as much a part of Rockwell's story as the "Sargent" and the "Picasso," however. A traditionally-dressed woman and her equally-traditionally-dressed daughter look at the Sargent; a young woman in jeans and boots looks at the Picasso. All three are holding symbolically important items: the girl's hand, a doll, and a sketchbook. At first glance, Rockwell gives us a smile as he shows us how people who defy traditional gender conventions enjoy art that defies traditional artistic conventions. He seems to be encouraging us, his viewers, to move along with the times and admire the young woman with her sketchbook while we dismiss the frumpy mother as old fashioned, stuck in the past.

Rockwell made a crucial error in his illustration, however, and the more I thought about it the more I began to see the painting as just another tired expression of the Male Gaze (Wikipedia actually has a good explanation of that critical term). The mother and child on the left reminded me of the many times I visited the Philadelphia Museum of Art with my mother, an artist, when I was in elementary school. Sometimes we were there so she could do some research for her own work (this was in the days before the internet, obviously); sometimes we were there just to enjoy the various exhibits on a rainy day. And we were always well-dressed – not "fancy" but definitely real shoes and dresses and a little extra effort on hair (both of us) and makeup (her).

Those are some of my fondest childhood memories, and I was in college before one of my roommates convinced me that it was okay to wear jeans to an art gallery.

Rockwell somehow didn't realize that there was no way that a "traditional" woman going to an art museum to look at Sargent paintings would have curlers in her hair or have left curlers in her daughter's hair. In 1966 (and for many years after!) curlers belonged only in the home or in the beauty parlor – they did not appear in public spaces, especially not in a space as formal as an art museum. In adding that incongruous detail to Picasso vs. Sargent, Rockwell over-played his hand and made the Sargent fans inaccurate and thus unbelievable.

Instead of an amusing comment on the way that fashion persists in clothing and in art, then, Rockwell has given us yet another instance of a man painting female figures to accord with his gendered vision of the world. Both the "Picasso" and the "Sargent" are presentations of the female form by male artists, and the three viewers are as well. All five women in the painting are created by male artists, and all are presenting femininity as an object "for the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer" (to quote the Wikipedia definition of the Male Gaze). Rockwell's pleasure in the mother is actually in demeaning her, in making fun of her curlers and dowdiness and conventionality; his pleasure in the young woman is in viewing her from behind, with her tight jeans and sexy boots.

In Picasso vs. Sargent, then, it seems like Picasso has won, with the prize of the young woman with the shining, loose red hair. Rockwell probably thought he was making a proto-feminist statement about the nascent movement for "women's lib" but here he has simply found a clever way to yet again present the female form as attractive object of the male gaze.

**with thanks to my colleague Donna Halper for finding a good-quality image of Picasso vs. Sargent**

Interesting interpretation! I did not get the male gaze idea at all, what I felt from it was a sense of repetition in history - the Sargent painting shows a woman in the oldest era, the Picasso shows a woman in the next oldest era, the woman in the curlers shows the older than ‘modern’ era looking at the oldest (traditional?) era, the redhead shows the ‘modern era’, looking at the second oldest era (rebellious?), and the little girl shows the future era, looking at the oldest era, but modelling herself after the older than ‘modern’ era.

I’m from the 90s where there was some influence in fashion from the 60s, and kids today have brought back fashion and culture from the 90s… When there is too much tradition we crave rebellion, when there is too much rebellion, we crave tradition. And we are always bringing things back from the past while also innovating for the future. I personally felt this painting was showing that culture is cyclical.

This painting does take place at the Art Institute of Chicago and my mother was the "model for the mom in curlers. My mother, Thelma Soderlind Heagstedt. worked in the publicity department at the Art Institute in the "60's. When Norman Rockwell visited she was in charge of taking him around and securing models for the painting he was planning. However, Mr. Rockwell did not like the model my mother hired and said he wanted to use her instead. He took her to Marshall Fields and bought her the coat in the painting. When he said he wanted her in curlers, my mother said that nobody would wear curlers to the Art Institute. He said, "lets go for a walk" and proved her wrong. My mother was shocked. I would love to get a print of this painting if you know a source. I spoke to the Rockwell Museum/historians a while back and they said the painting is in a private collection. I do have a tear sheet from the issue of Look Magazine and have done some prints but they are very poor quality. He captured my mother so well, she is very recognizable. Unfortunately I used to have a thank you note that he wrote to her, but after many moves it seems to have gotten lost.