OK, this week the obvious focus of our attention is Ulysses / Odysseus in Canto 26, another one of those frequently-anthologized segments of Inferno that you may have encountered before as a stand-alone.

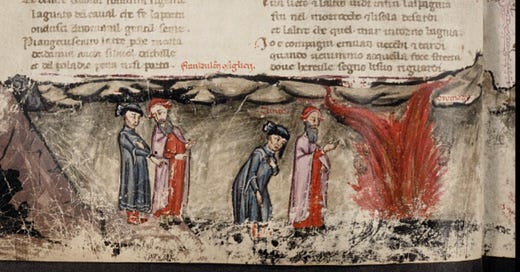

Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Holkham 48, f.40, from digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

At the risk of belaboring the obvious: we have in Canto 26 an echo of Dante's earlier placement of himself among the great Epic Poets (remember Canto 4?) in that the three generations, as it were, of Epic Poets meet here. Ulysses is the Latin/Italian name for Odysseus, the hero of Homer's Greek Odyssey (and the subject of the summer 2018 online reading group, with introductory post here, in case you're interested). Virgil is here, as well, obviously, and he's the author of the Latin Aeneid, the epic of Aeneas and the founding of Rome. And then we have Dante, the pilgrim/character and the poet of the Comedy, who is pretty definitive about placing himself in this patrilineal, poetic genealogy. For a much better analysis than I could ever provide of the understanding of epic heroes in our fraught historical moment of the summer of 2020, check out Tayla Zax's NYT essay about new translations and analyses of epics (shoot me an email for a PDF if you’re not an NYT subscriber).

So what is Odysseus doing this deep in Hell? Why isn't he up in circle one with the virtuous pagans, if he's a "hero"? Pouch 8 of the eighth circle is for "False Counselors," and part of Odysseus's sin seems to be the deceit he devised and used to win the Trojan War -- the "gift" of the Trojan Horse, with the Greek warriors hidden inside. Odysseus and Diomedes "grieve for their device, / The horse that made the doorway" (26.60-61).

I was thinking about our discussions of how parts of the Inferno haven't "aged well," and I'm wondering if we are seeing here a 700-year-old version of the same phenomenon. Homer and other ancient poets praise Odysseus for his strategic skills -- he is "wily" or "crafty" (depending on the translation), and he is the protagonist that we're cheering for as he outwits the Trojans or the Cyclops or the suitors courting his wife. But now (in 1320 CE) Dante seems to be re-evaluating Odysseus's craftiness and counting it as "false counsel" rather than "smart planning." Perhaps for Dante the poet, parts of the Odyssey haven't "aged well"?

Furthermore, for the modern reader, Odysseus here is inflected by Tennyson's Ulysses. A classic undergrad essay question about this poem is to think about whether Tennyson's Ulysses is heroic (I confess: one of the options on Lesley's English Lit II midterm for many years), and the core of the tension in Tennyson's poem is here in Dante as well. Is he a heroic explorer or an irresponsible deadbeat? Dante's Ulysses tells us that he was driven by "My longing for experience of the world" (26.94), which seems like an admirable and relatable goal; a few lines later, he encourages his sailors with the lure of "the pursuit of knowledge and the good" (26.115). Who DOESN'T value 'experience of the world' and 'pursuit of knowledge'? And yet Odysseus drowns (the dramatic finale of Canto 26) and ends up encased in a flame in the eighth circle of Hell. What’s happening here, literarily and theologically?

Other possible items for discussion:

In his notes, Pinsky provides a substantial analysis of the horror of the snake-transformation/absorption in Canto 25 ("uncanny transformation of the human body," p.411). Did you find it as terrifying as he does? How/does Canto 25 mesh with the fear induced by good horror films?

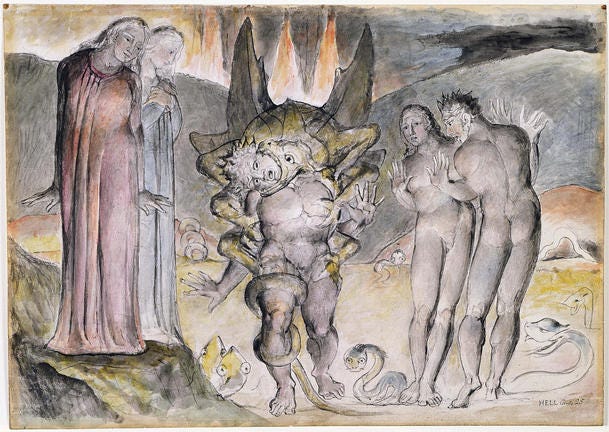

William Blake, illustration to Canto 25, from blakearchive.org

Leaving aside the questions specific to Ulysses/Odysseus, why might engulfment in a flame be an appropriate punishment for a false counselor? Does this punishment "fit the crime"?

Did you notice the amazing firefly simile at 26.27? how/why does the comparison work and what associations does it imply?

The first time I read The Divine Comedy I was very focused on the mechanics of the afterlife as Dante presents them, so I think I ended up missing a lot about the various figures the pilgrim encounters on his journey. Trying to pay more attention to that this time, the thing that struck me the most about Odysseus’s inclusion in the narrative (at all, not just in Hell specifically) was that he’s a literary character. So many of the residents of the Inferno are individuals who the author had a personal or political grudge against. I didn’t properly register that there were fictional characters in his Hell until this past week. The Divine Comedy is petty in the most delightful way possible. That pettiness has sort of become a staple of Dante for me, and creates a partial framework that Odysseus exists outside of.

My instinct when reading the question “what is Odysseus doing this deep in Hell?” is to say ‘well, Odysseus is a bad person.’ That was the basis for most if not all of my responses to the 2018 reading. I am less caught off guard by his presence in deeper Hell than I am by Dante’s failure to address the things that would have damned him. In the original epic, Odysseus is a murderer (and not just in the context of battle), a sexual predator, and promoter of the slave trade. In regards to how the way that The Odyssey aged for us compares to how it would have aged for Dante: it almost feels like Dante is in the process of moving toward figuring out how messed up Homer’s work actually is, but he doesn’t quite get there, and that’s weird to see as a reader.

I’ll also add that Dante deciding to basically add an epilogue to The Odyssey feels almost like a step beyond just putting himself in the company of other great poets. It’s not just ‘I met Homer and he saw me as a kindred spirit’, it’s ‘I am going to full on take over one of the world’s most famous literary characters, and decide his ultimate fate.' It kind of like Blake claiming to be able to speak for Milton.

*Every time I read Dante I make myself a map as I go. I don’t know if this will be helpful for anyone else, but pairing the action of creating something with my progression through the book has done much more to orient me within the story than looking at pre-existing maps for reference.