The Massachusetts Medievalist on the end of Inferno, Cantos 31-34

The end of Inferno is both climactic and oddly disappointing. The pit of ice encases varieties of betrayers - those who betrayed their families, their countries, their guests, and their mentors. As we pass through the segments of the ice pit, we hear the horrific story of Ugolino, another frequently-anthologized section of Inferno; part of Ugolino's sin is his mis-reading of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. The stories of Abraham and Isaac (Genesis 22), the Last Supper (Luke 22), and Crucifixion (Luke 23) also engage with powerful fathers (Abraham, God) and the sacrifice and consumption of sons (Isaac, Christ) - but of course Ugolino does not understand the ways that the Biblical texts point readers to Faith, while his choices point only to Hell.

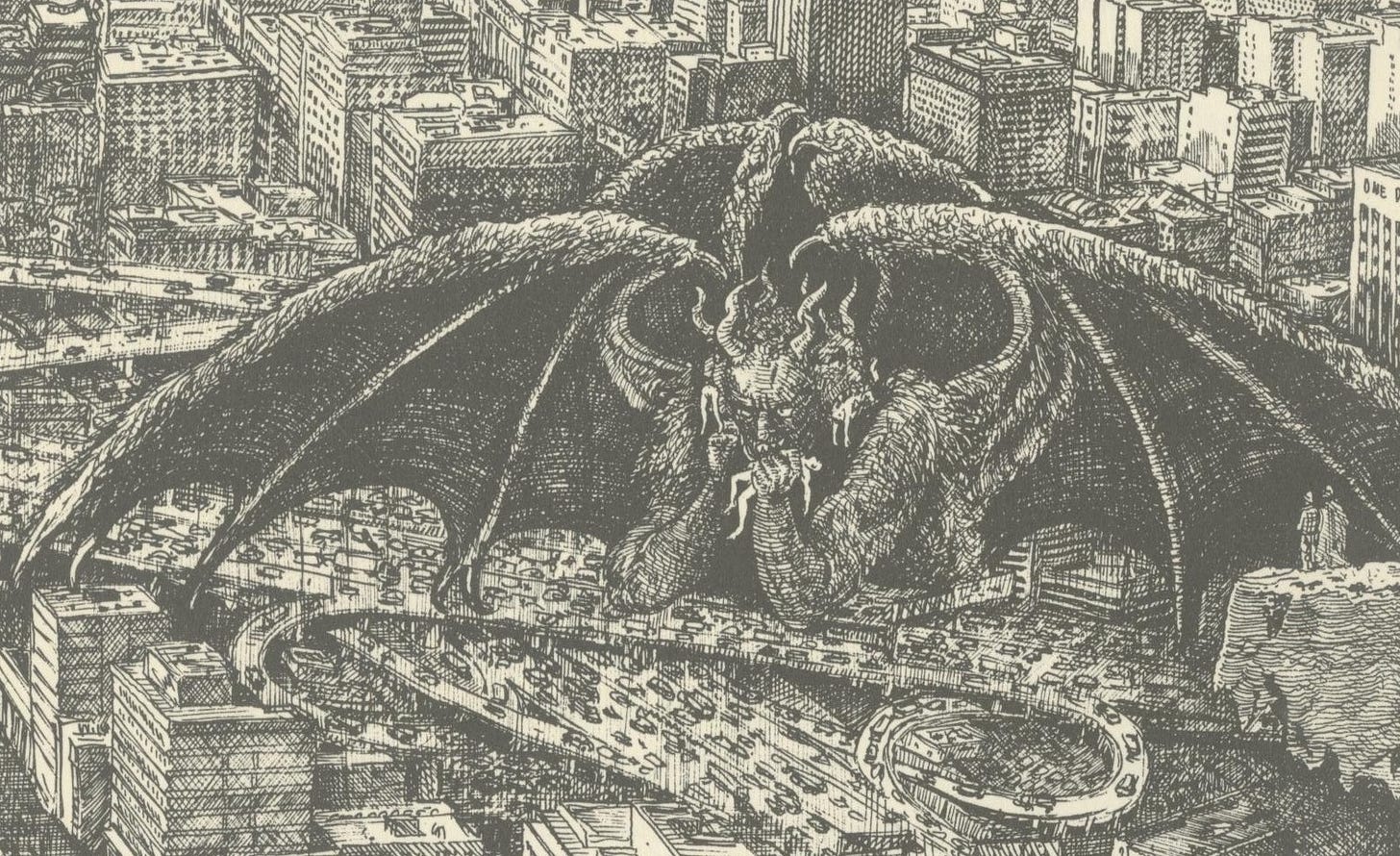

Birk, Canto 34 (detail), from digitaldante.org

Satan/Lucifer, of course, is the most terrible of these traitors, since he betrayed God, and he is appropriately gigantic and monstrous, so enormous that he dwarfs the giants ringing the Pit. Satan has three faces, a detail usually interpreted as a monstrous inversion of the Holy Trinity of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In this summer of Black Lives Matter and ongoing calls for racial justice, I was struck instead by the racially-inflected descriptions of Satan's faces: one face is red (34.42), one is "a shade / Of whitish yellow" (45-46), "the third had such a mien / As those who come from where the Nile descends" (46-47). Only the Black face is specifically, geographically localized (to sub-Saharan Africa -- remember that the Nile flows from south to north). The images of Satan reproduced here present these three faces in a number of different ways - and don't forget the lovely structural balance this three-headed Satan makes with the three-headed Cerberus we met way back at the beginning of Hell.

Oxford, Bodleian Library Holkham MS 48, f.53, from bodley.ox.ac.uk

One potential Christological analogy that then additionally presents itself for this multi-raced Satan is a reference to the Three Magi at the Nativity. The three kings were understood as representative of the three continents of Europe, Asia, and Africa (if you're interested in the three continents and medieval maps of the world, this British Library blog post is a good place to start). The theological implication of the racially diverse Magi is that the power of Christ reaches the entire world -- so maybe the multi-colored Satan implies that the power of evil and betrayal is also worldwide? I couldn't find any scholarship confirming this idea, however, so that's a very hesitant suggestion.

London, British Library Yates Thompson MS 36, from worldofdante.org

The logistics/physics of the bottom of the Pit are spectacular -- literally! -- in the sense that I would love to watch a very good CGI film version of this scene. The Yates Thompson illustration just above gives the best sense of what happens at this point: Virgil and Dante climb down Satan's torso: they "From tuft to tuft descended through the mass / Of matted hair and crusts of ice" (34.73-74). They reach the exact center of the earth, "the pivot of the [Satan's] thighs" (34.75). Even though Dante the Poet did not have scientific language to describe gravity, he imagined that at this spot the force of gravity would invert so that Dante's and Virgil were suddenly upside-down (enjoy the upside-down Satan on the right of the Yates Thompson miniature). This gravity-inversion forces forces Virgil to execute an incredible strength move: with Dante on his back, "with strain / And effort my master brought around his head / To where he'd had his legs" (34.76-78) so that they are able to climb up out of Hell. Inferno then ends with the word stelle, stars, just as its companions Purgatorio and Paradiso do.

Now it's time to take a deep breath and process this 4720-line poem before we turn our attention to another literary monument: Morrison's Beloved. To return to our focus throughout this summer on the characters of Dante and Virgil: does Inferno follow the traditional narrative arc? To phrase that question in another way: does Inferno provide exposition, rising action, climax, and resolution? Does Dante the Pilgrim change and grow -- is he a dynamic character? Is Virgil the inadvertent hero of this epic (looking at you, Kristen Amato…..)? What are your thoughts on completing this ultra-canonical text?

I am so torn! Is Dante the hero of this story? I'm not sure. Dante the Poet clearly wrote Inferno with himself as the hero in mind, but I can't help but compare him to the heroes of greek epics such as Odysseus, who is clearly a stark contrast. Dante doesn't fit the mold of the typical epic hero; he doesn't possess superhuman strength or unwavering courage. He heavily relies on Virgil throughout the entire poem to calm his nerves and protect him from the evils that surround him. The thing that struck me while reading this was how flawed Dante is, but that makes him more a more relatable and likable character than, say, an Odysseus. He struggles more internally with his own morals and beliefs as opposed to facing outer demons which is honorable and relatable in its on right, but is it heroic? I'm not completely sure.

After reading this entire poem, I'm still very much intrigued by the entire concept. Going into the text, I knew the general idea, but I was excited to read the details and be immersed in the circles of hell. In the end, however, I found it very hard to read and had to constantly refer to summaries to help me sort out what was happening. This took away from some of those climatic moments for me. I wasn't able to fully be immersed in the world of hell because I was so focused on deciphering the language. I would love to see this as a movie - Dr. D, your references to some of the scenes being brought to life on the big screen had me picturing it in my head as an epic, action-packed journey which I would be very keen to see someday!

I am very much looking forward to Beloved next week!